Songwriting For Music Producers: Understanding Melodies, Pt. 2

After having discussed chord tones and non-chord tones, and how to write better meldoies. it’s time to talk about the other factors that make a strong melody.

From the very foundations of a melody such as motifs to central elements such as motion, space, and rhythm, we’re breaking down what makes a great melody so that you can start writing awesome melodies of your own.

Motifs and Melodies

When you’re sitting at your piano roll, you can see the structure of 4/4 time. Well, that’s if you’re writing in 4/4 time.

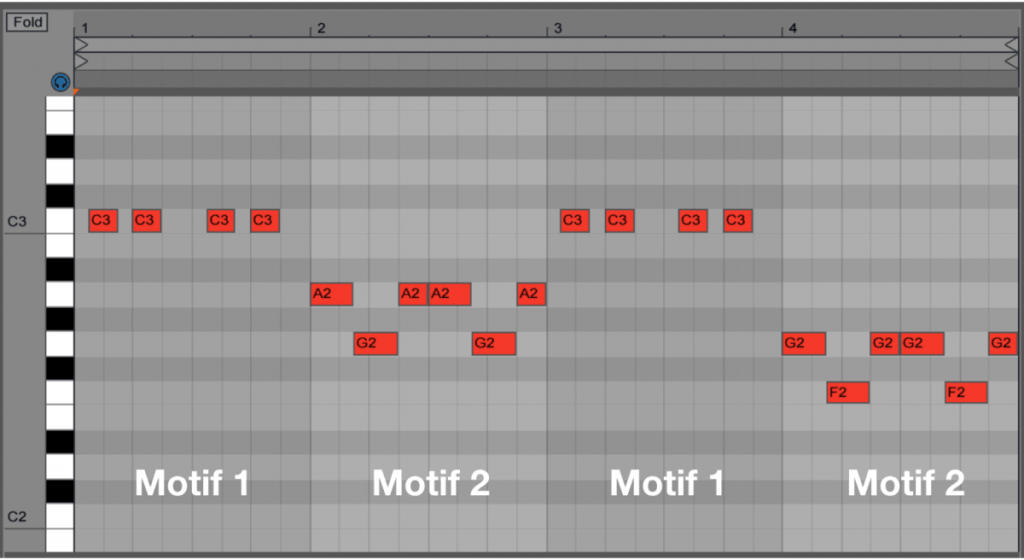

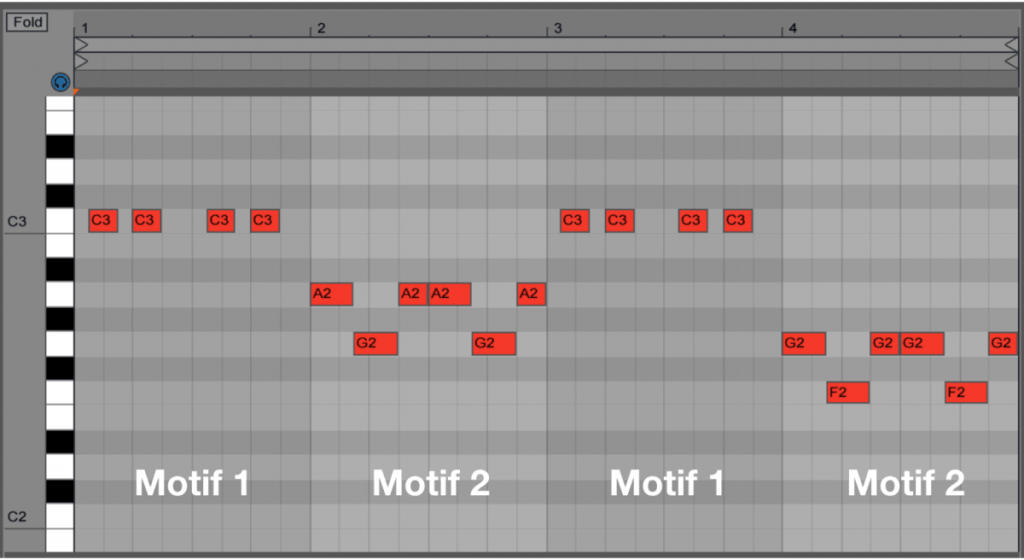

In the image above, you can that in each bar we have an individual motif. There’s a group sequential of motifs together too. A motif consists of a couple to several notes that relate to one another in meaningful ways. In the example above, a total of 3 motifs have been used to make up a full melody.

There are four motifs here, but motifs 1 & 3 are the same, and motifs 2 & 4 have the same rhythmic pattern (more on this will follow) but the notes are different. A melody can be but doesn’t have to be made of multiple motifs that we repeat and tweak to create a musical idea.

Building a melody with motifs simplifies the process. You could use motifs anywhere in your music as a short musical piece. They don’t need to be sequential or make up a full melody. A melody that makes use of motifs is called a motif-based melody.

Motion of a Melody

When writing a melody, there are two kinds of motion that you can use.

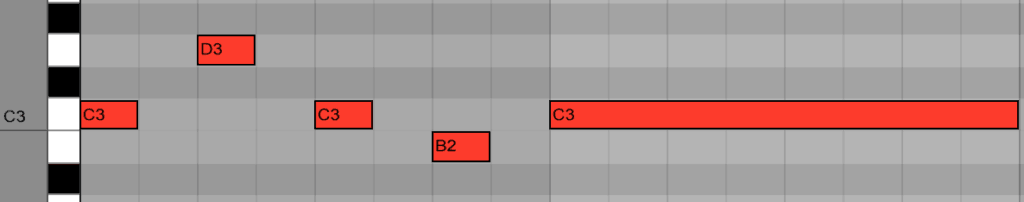

Stepwise motion occurs when you play a note that’s next to your previous note in the same scale.

A leapwise motion occurs when you jump to a note that’s more than one note away in the same scale.

As the same with chord tones and non-chord tones, a strong melody has a balance of both leapwise motions and stepwise motions. A stepwise motion is easier to follow compared to a leapwise motion, so when deciding what note to play next consider both your personal taste and style of music.

A strong melody has a balance of both leapwise motions and stepwise motions

At the same time, in music, we learn the rules to break the rules. If what you’re writing doesn’t correspond to your preferred genre(s), but you really love where the idea is going with your stepwise motion, keep it. You never know, you could change the genre or create a whole new one.

Space in Your Melody

Again, having the right amount of space between notes comes down to balance. Space is an integral part of a great melody. Using too many notes will make the melody difficult to remember as it’s too complicated, but using too few notes makes the melody boring.

Do you see? Balance!

There’s no right amount of space. It’s completely subjective to your current project and depends on the style of music.

Your average listener wants a clear and simple melody line to follow and focus on. So, filling up the piano roll with notes is detrimental to that effect. Focus more on the space between your notes rather than the notes themselves. Don’t make it too complicated or boring!

A handy tip, though, is to keep your strong and weak beats in mind. If you have a busy melody in bar 1 and your listener is expecting a note on the first beat of the next bar, t’s a handy trick to delay that note for 16th of a note. This creates s a gap and thus creates interest and tension!

Rhythm in a Melody

Your listener enjoys following a simple melody, and they enjoy following a simple rhythm too. Having 2-3 individual rhythmic patterns (motifs) in a melody is safe, and your melody will be simple to remember for your listener.

You can experiment with more of course, but we’re keeping this explanation simple. Experiment and see what you find.

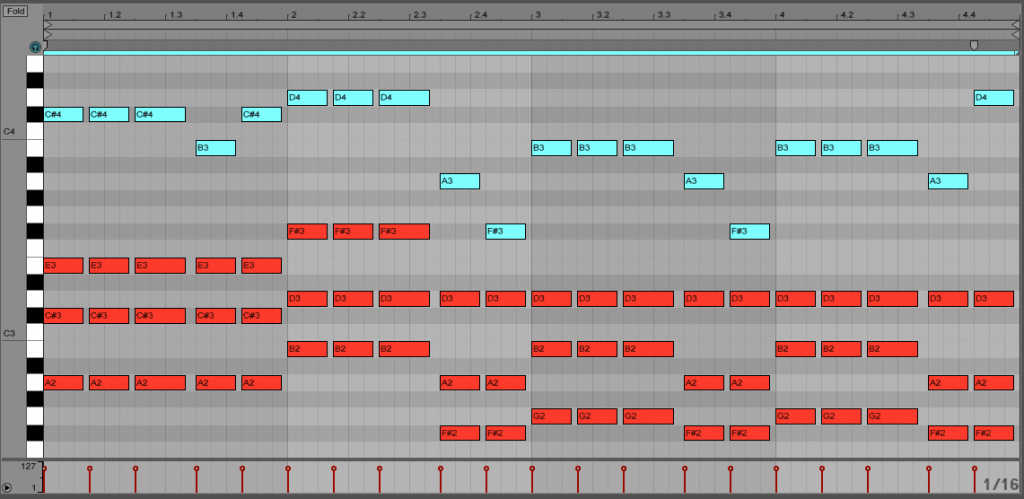

When writing rhythmic patterns, rhythm corresponds to time. If you write two different motifs that hit different notes but the timing of the notes is the same, they have the same rhythmic pattern.

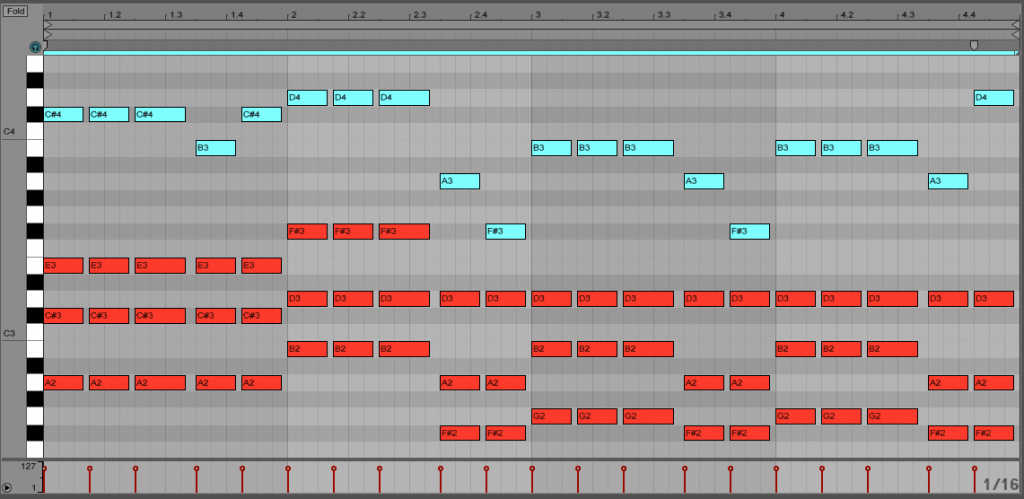

The rhythm of the melody and the chords in the image above are the same. They hit different notes, but the notes it at the same point every time, thus making the melody very easy to remember.

The rhymic pattern of the melody and chords is also the same in every bar. The notes themselves change, but the timing of the notes stays the same.

Finally, Melodic Repition

Repetition is a huge part of the job when developing a melody. Repetition allows our listeners to get familiar with our melody. When we were discussing motifs and rhymic patterns above, we’re sure you noticed some repetition.

There are 3 main ways that we can repeat a melody, and these are:

Melodic Repition

Melodic repetition is when, you guessed it, the melody itself repeats.

Using our motif example, you can see that the third bar repeats the first bar. This is melodic repetition.

Melodic repetition is a great tool, but using too much of it can make your melody plain and boring.

Rhythmic Repition

As it’s fitting, the image we referenced to describe rhythm is also great for describing rhythmic repetition.

When you play different notes that follow the same rhythm as a previous bar, you’ve undergone rhythmic repetition. Rhythmic repetition is an awesome way to develop your motifs into musical melodies.

Contour Repetition

Melodic repetition is when the exact same melody repeats – pitches and all. Rhythmic repetition occurs when different notes are used to play the same melody.

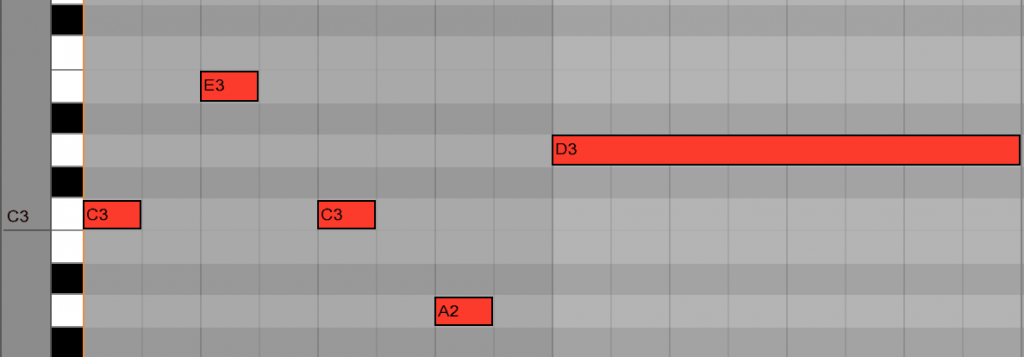

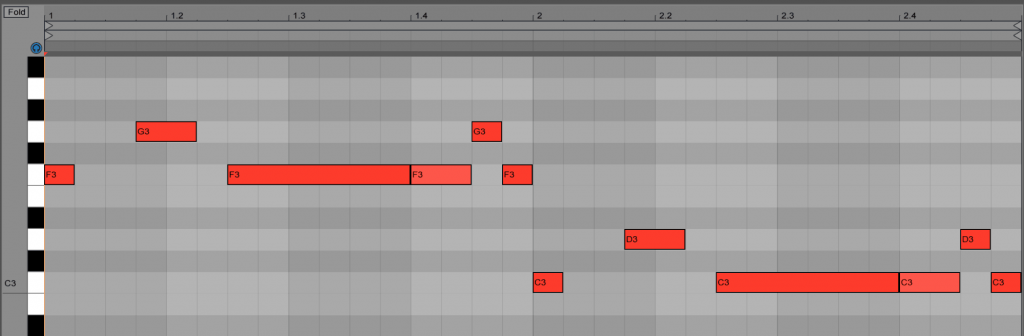

But melodies can repeat contours. A contour is the outline of a shape. So, with this in mind, contour repetition is when the same melody plays but at different pitches.

You will have noticed that the melodies we’ve displayed and the ones you’ve made have a shape in your DAW. They rise up, fall down, and make jumps up and down too.

So, with contour repetition, you’re repeating the same melodic shape. The only reason it differs from melodic repetition is that contour repetition repeats the same melodic but on different notes as you can see below..

This makes the 2nd bar feel familiar, despite it playing a different melody line.

In the Mixxed sample library, you’ll find a huge array of melodic samples that are DAW-ready.

The sampling revolution has risen in popularity and shaped music since the early 1970s. Sample culture continues to transform how millions of artists and producers do their thing in DAWs.

You too can break conventional norms, challenge the status quo, and open Pandora’s box of sound design.

Mixxed works with a growing number of sample labels and contributors to provide you with an affordable sample subscription service that’s more accessible than any before.

You’ll have access to our growing catalogue of loops, one-shots and sound effects that you can browse, download and keep forever for less than $3 a month.

Sign up today to find your sound!